By Hilbert Haar / TODAY NEWSPAPER

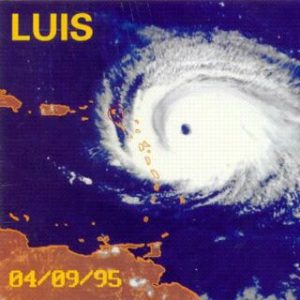

GREAT BAY – “I did not know what a hurricane was. I was in the radio business and I thought, I am going to drive around. I was on Bush road when at 3 p.m. all hell broke loose. I saw one of those heavy freezers that stand in front of supermarkets twenty meters up in de air. That’s when I got scared, I thought I was going to die.” It happened on Tuesday, September 5, 1995, tomorrow exactly twenty years ago. The radioman was Glen Carty, nowadays interim director at social insurance agency SZV and the manager of UTS Eastern Caribbean.

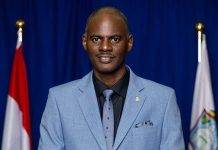

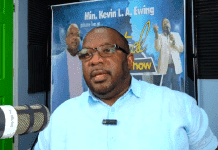

Today sat down with Carty and with Dennis Richardson, at the time the Lt. governor of the island territory, and currently our minister of justice, to mark the twentieth anniversary of Hurricane Luis.

Shortly before he saw that freezer fly through the air on Bush Road, Carty heard the broadcast at Radio 101, housed in the building in Madame Estate where now Laser 101 is located. Behind the mike was a young man with one of the finest broadcasting voices on the island – Cedric Peterson, currently employed at the government department of communication DCOMM. “I heard a lot of noise in the mike and I asked Cedric what was going on,” Carty remembers. “The roof is coming off, Cedric said. Not in pieces, but in one go.”

Lt. Governor Richardson was at the government administration building on Clem Labega Square with his wife. “I was there to help organize everything and to take decisions. That is where we weathered the storm.”

It was a wise decision to hold up in then government administration building. “I could not go back to my home. It was empty, there was nothing in it anymore, Tables, chairs, beds, clothing, and everything was gone. It was like somebody had come in, took everything away and cleaned up afterwards,” Richardson says

While some reports mention that Luis hung around for three full days after its devastating arrival, Richardson and Carty say that the real bad part of the storm lasted for twenty hours.

Carty notes that Richardson earned the nickname Mr. Hurricane during his tenure as Lt. governor. “He went through one hurricane after the other.”

Between 1994 and September 2000, the span of Richardson’s tenure, the island saw hurricanes Luis and Marylin in 1995, Bertha in 1996, George in 1998, José and Lenny in 1999 and Debbie in 2000.

Carty ended up in the EOC (Emergency Operations Center) back in 1995. “How I got there I don’t remember; I was in the radio business. We saw Luis come at us, we saw the storm grow, and we saw it heading straight for St. Maarten. To get storm-information faster, I went to sit down in the government administration building. This is how I became friends with Dennis – we did not know each other at the time.”

St. Maarten was not really prepared for a major hurricane back in 1995. “The EOC did not function properly,” Richardson remembers. “I attempted to convene a first meeting, but the people were not speaking with each other – the police, the fire department, but also people in the civil service. There had been few exercises and meetings. You saw how people who had a certain task disappeared into the background, while others who did not have those tasks stepped up to the plate. That is remarkable. In spite of everything you’ll find people ready to do the job. I am not going to mention any names, because all those people are still alive. What matters is that we had an EOC that formed spontaneously and organically, based on what had to be done.”

On Monday evening, the night before Luis would turn the island into a pile of rubble, Carty was at a meeting of the EOC. “It was a small group,” he recalls, “and I felt the tension. We talked about body bags. I don’t know where the number came from but someone said that we needed 300 body bags. And we needed a freezer container, because we thought we were going to lose power and we had only one funeral home, near the library, with maybe three freezers.”

When Carty went home after the meeting it suddenly hit him: “This is going to be bad. Those two expressions – 300 body bags and a freezer container – that made my hair stand on end, still today. We thought we were prepared for possibly 300 casualties. That’s when it became scary for me.”

There were in the end just nine casualties – seven people drowned on the Dutch side, and two died on the French side. Luis, reached wind speeds of 203 kilometers per hour and caused $1.8 billion in material damages to the Dutch and French side of the island combined. The storm left 7,000 people homeless; in the Simpson Bay Lagoon, 1,300 boats sank.

The island territory had a disaster plan, Richardson says, but that was about it: “There were hardly any disaster exercises, but people who had gone through previous hurricanes helped us a lot. We announced tips we received from our parents and grandparents via the radio. That has played a part in limiting the number of casualties.”

Among those tips was this one: if you have to leave your home to go elsewhere, don’t walk upright. Stay as close as possible to the ground; crawl. Another tip was to hide in the bathroom, the smallest and usually strongest room in a house.

“All those things that we did not have pinned down came up in a single brainstorm session,” Richardson says. “We broadcast them on the radio and people applied them.”

News about the aftermath of the hurricane varied wildly. Some newspapers reported more than one thousand casualties. Richardson: “That number stems from a scenario they played out in the Netherlands based on the particulars of the storm. That exercise showed that there could possibly be more than one thousand dead.”

That number did not ring true with the people on the ground. Carty: “Nobody could tell us – we miss that many people. Because of the continuous information we provided, people were well prepared. 80 Percent off the homes lost their roofs, but people managed to find shelter. From that day on we said at Laser: there has to be a storm watch team for every approaching storm to give more information. It is essential.”

When the storm hit, all radio stations went off the air. “There was nothing we could do,” Carty says. “The next morning all radio stations got together. I collected what I could from Laser and we set up emergency radio station 101 in the parliament building on Back Street.”

Without computers, the station was on air 24/7. “We did shifts; Eddie Williams had the morning shift, and everyone cooperated,” Carty says, “I noticed that then, there was no difference between black and white, rich and poor, catholic and protestant. Everybody was working for a common goal – and that is something I miss these days. Back in 1995, we had a natural disaster, now we have man-made disasters. I miss the togetherness, the preparedness to set differences aside and to work towards that common goal. That helped us a lot at the time.”

Luis wreaked havoc in the island’s shanty towns that were soon to become a political problem, because Richardson intended to erase them. “We got visits from Curacao and later from the Netherlands; they were all opposed to bringing the shanty towns down,” the former Lt. governor says. “In the Netherlands they wrote how inhuman is would be to do this, when Dutch journalists came here I put them on a bus and sent them through the shanty towns. When they came back they apologized to me.”

Richardson asked for ‘hard’ military assistance. “We expected trouble when we went in to take down the shanty towns. The Netherlands refused to send in the military and in the end we put two police officers there and we did it anyway.”

Carty went up to the shanty towns with an ambulance of the Wiems, the Windward Islands Emergency Medical Services. “I wanted to see in which circumstances people lived there. It was incredible. I had never seen anything like it.”

Richardson declared the state of emergency during Luis. “I had a lot of power because of it,” he remembers. “If you had the guts as Lt. governor you could do a lot of things. We confiscated water from the supermarkets for instance, to guarantee adequate distribution, and we build an emergency road along Divi Little Bay to bring supplies to Philipsburg.”

Luis has definitely changed St. Maarten, Richardson says. Houses built after the hurricane are of a better quality and building regulations were more strictly enforced. Citizens who had suffered damages to their homes did not need any encouragement: they built sturdier homes under their own steam.

Putting all cabling underground did not happen: it would have taken years to do this, and the priority was to get the country back on its feet as soon as possible. “We decided that from there on, cabling for new projects had to be underground. That is done up to this very day,” Richardson says.

Schools also came out ahead: “I used negotiations with the Netherlands to obtain financing for a school construction program. With good technical assistance that has improved the situation of our schools.”

Luis is now part of St. Maarten’s history, but for those who lived through it, this particular hurricane has become a part of their lives.

“It is deeply ingrained,” Richardson says. “A year after Luis I gave a presentation in Amsterdam about disaster management. I made the same presentation at the Great Bay Hotel later. Part of it was a recording of the sound of the wind Luis produced. People started to cry when they heard it. Several people have left the island the day after the hurricane, and they never came back.”

The support from Dutch marines after the hurricane was crucial for the reconstruction efforts. “It was very important that they were here, because the population was in shock,” Richardson says, “The marines began with a large cleanup. Their example brought people out of their state of shock and then everybody began to take part. The marines did a tremendous job clearing up the mess.”

Luis produced its crop of local heroes, and Carty remembers one in particular. “His name is James Marlin and he was somebody who repairs generators. He was very sick, he had a urine bag hanging under his shirt. But he was sitting there, repairing generators after the storm. Those slavery statues at our roundabouts are important but for me, this man is also a hero.”

Physically the island is better prepared for a major hurricane, if only because the quality of buildings has strongly improved. What about the organization though?

“I dare not say that that has improved as well,” Richardson says. I know that Clive Richardson puts an enormous amount of energy into it, together with Paul Martens, but I have no insight in how it functions today.”

Richardson is however aware of an evaluation meeting after the passing of Hurricane Gonzalo last year. “The general opinion was that the emergency center had reacted inadequately to the situation. They underestimated Gonzalo. They were honest about their assessment, like the cleaning of trenches. There are a number of things that you have to do ahead of a hurricane anyway.”

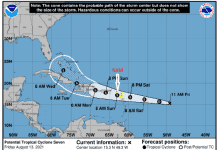

How true this is appears from the island’s preparations for the arrival of Tropical Storm Erika. At the very last moment contractors were busy with cleaning trenches – something that should have been done a long time ago.

“It is a difficult call to close down the island,” Carty acknowledges. “I always refer to August 1, 2005, No hurricane, no tropical storm, no depression. But we had a cloudburst over Saunders and two people died. We live in an area where these weird things can happen.”

Carty says that every company should have its own disaster plan, one that takes employees and their families into account. “I always say: be self-supporting for the first three days after a hurricane, but you cannot leave everything in the hands of the government. We need more education about this issue; people see it, but somehow it does not register.”

Richardson refers to priorities in the strategic decisions that have to be taken. “Port, airport and main roads. Period,” he says. “They have to be cleaned up otherwise you cannot move anywhere. For me it was important, though I took some flak over it from the governor, to have an assessment of the situation as soon as possible.”

Richardson refers to priorities in the strategic decisions that have to be taken. “Port, airport and main roads. Period,” he says. “They have to be cleaned up otherwise you cannot move anywhere. For me it was important, though I took some flak over it from the governor, to have an assessment of the situation as soon as possible.”

Luis had hardly left town before Richardson jumped in a police car to have a look around. The situation was bad in Pointe Blanche, and over the hill towards the airport. “You knew that you had an enormous disaster on your hands. You need that insight otherwise you are going to take the wrong decisions.”

Carty’s concern about the current situation – twenty years without a hurricane of Luis-like dimensions – feels real: “What makes me a little bit fearful is that we have a generation that never went through a real hurricane,” he says. “The EOC looks good on paper, it has a structure. But you don’t know what the people who are sitting at that table are going to do when the shit hits the fan. Almost nobody in this group has gone through Luis – that kind of event separates the boys from the men. They are book smart and you are only going to find out how they react during a real event.”

People in responsible positions, like Lt. Governor Richardson, have to deal with other aspects too: “You have to go against the tendency of the private sector where they want to remain open as long as possible. You get that pressure, also because we are a tourist destination. I understand that but at a certain moment you have to say – now it is over. I take my responsibility and we close down. It is not only about money, but also about the safety of personnel. They all have families that need protection and houses that need to be boarded up.”

Carty has a deep respect for Richardson’s hands-on approach to crisis situations. He recalls a moment during another Hurricane (José in 1999) when a report came in about a landslide in Oyster Bay. Carty took his four-wheel drive to the location, but Richardson came along, together with Michael Kuiperi, at the time one of Carty’s colleagues.

At the location, they found a home full of mud and a collapsed retaining wall behind it. “The backdoor was open and we wondered what had happened,” Carty recalls. “We started digging in the mud with our hands – and the Lt. Governor was digging with us. There we found a man with his eyes open, dead.”

“You have to experience it, you have to get your hands into the earth,” Richardson adds.

For Carty, Luis was a blessing in disguise. “It is the best university I have experienced,” he says. It taught me to plan, to manage and to take decisions. It was a good school for me. It is about saving lives and knowing that if you make a mistake it could cost someone his life.”

“In my position,” Richardson says at the end of our interview, “I had to take decisions too. You are throwing the bureaucracy out the door. We are reacting faster every time. Practice makes perfect.”