Steve Kroft reports on how cash-starved countries offer citizenship for a price, creating ways to ease travel for foreigners, including those running from the law.

60 Minutes

The following script is from “Passports for Sale,” which aired on Jan. 1, 2017. Steve Kroft is the correspondent. Graham Messick and Evie Salomon, producer.

If you have been thinking about leaving the United States, moving to another country and changing your nationality, it’s never been easier to do. In this era of globalization, citizenship and passports have become just another commodity to be bought and sold on the international market. All you need is money and a willingness to contribute a few hundred thousand dollars to the treasury of a cash-starved country or acquire a piece of real estate there.

It’s called citizenship by investment and it’s become a $2 billion industry built around people looking for a change of scenery or a change of passport, a new life or maybe a new identity, a getaway from the rat race, or perhaps an escape from an ex-spouse or Interpol. In any event, it’s brought in huge amounts of revenue for the sellers and attracted among the buyers a rogue’s gallery of scoundrels, fugitives, tax cheats, and possibly much worse.

If you’re shopping for another passport, the top of the line right now is Malta. By investing a million dollars in this Mediterranean island, a Russian or Chinese or a Saudi can become a European citizen with a new EU passport that will allow them to travel just about anywhere without a visa. There are also much cheaper, less discriminating alternatives available in the Caribbean, especially on the tiny island of Dominica, where Lennox Linton is a member of Parliament.

Steve Kroft: How much does it cost to get a citizenship?

Lennox Linton: $100,000.

Steve Kroft: Do you have to come and live in Dominica?

Lennox Linton: No. No. You don’t even have to come to Dominica to get the citizenship. You pay the money from wherever you are.

Steve Kroft: Sorta just mail order citizenship?

Lennox Linton: Sort of. Something like that.

Our introduction to this world of citizenship by investment came in Dubai – the gleaming, international bazaar – that was hosting the ninth annual global citizenship conference. Gathered here were government officials, lawyers, bankers, and real estate developers who facilitate and profit from the trade of citizenship for cash.

Chris Kalin: Good evening, and a very warm welcome…

This is the man who more or less invented the business: Chris Kalin, chairman of Henley and Partners, a consulting firm with offices, where else, but in Zurich, Switzerland. For a fee and healthy commissions, Kalin helps countries set up their program, rewrite their citizenship laws, and recruit people of means looking for a second, third, or fourth passport, which he sees as just another travel accessory; a passport of convenience.

Chris Kalin: You probably have more than one credit card, I would assume. And, you know, if Visa doesn’t work, Mastercard will do. So I think any wealthy person nowadays should have more than one credit card. And likewise, you’d have more than one passport.

Steve Kroft: But you need to have some money to do this?

Chris Kalin: Yes.

Steve Kroft: To be able to do this?

Chris Kalin: Yes, absolutely. It’s just for wealthy people, of course, yeah.

Quite often these wealthy customers come from politically problematic countries where their passports don’t work very well, making it difficult for them to get where they want to go. Global citizens like international lawyer Sirous Motevassel, a Middle Easterner from Iran who travels on a West Indian passport from St. Kitts and Nevis.

Steve Kroft: And where do you live?

Sirious Motevassel: I’m living in Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

Steve Kroft: So you’re an Iranian living in Dubai with St. Kitts citizenship.

Sirious Motevassel: Yes. Yeah.

Steve Kroft: That’s complicated.

Sirious Motevassel: Yeah. It, yeah. This is the life.

It’s the life, because Motevassel’s St. Kitts passport, available for $250,000 or a $400,000 real estate investment, allows him entry to more than 100 countries without having to get special permission. It’s a legal way to circumvent visa controls that nations set up to screen people coming into their country. But it’s also an opportunity for shady characters to mask their true identities, and avoid suspicion as they travel around the globe. The business was born here in St. Kitts when Chris Kalin struck a deal with the government a decade ago following the collapse of the islands’ sugar industry.

Since then, passports have become its major export, providing hundreds of millions of dollars in income. In fact in 2014, the last year for which there are government statistics available, 40 percent of the government’s revenue came from selling passports.

It’s provided St. Kitts and Nevis with hundreds of millions of dollars for infrastructure projects, private development, and tourism but a lot of the money is unaccounted for. More than 10,000 people have purchased citizenship here, but it’s almost impossible to tell who they are because the information is not public. Chris Kalin doesn’t like the words citizenship for cash, or any suggestion that all you need is money to get a passport.

Chris Kalin: You have to go through a process. You have to apply. And you have to answer a million questions. And you have to undergo a background verification. And you have, at least in the properly run programs, you have to be a reputable person. And that’s checked.

But evidently, not that carefully. About the only way to identify people who have purchased St. Kitts citizenship is if they happen to turn up on a list of international fugitives or get in trouble with the law, and St. Kitts and Nevis has more than its share for two sleepy, little islands. Its passport holders include a Canadian penny stock manipulator… a Russian wanted for bribery… a Kazak wanted for embezzlement… two Ukrainians suspected of bribing a U.N. official… and two Chinese women wanted for financial crimes.

Chris Kalin: I think it’s no secret that these islands have made decisions that are not always optimal.

Steve Kroft: They’ve taken some bozos, as you would call them?

Chris Kalin: Yes, exactly.

Steve Kroft: What about crooks?

Chris Kalin: Yes. It’s goes all the way down to crooks, yeah, absolutely. And it tended for some time to attract quite a few people that I would never let into the country. But I’m not the government of St. Kitts and Nevis.

Steve Kroft: But you set up their program.

Chris Kalin: We helped to set up the program. But, you know, as it is, advisers advise, ministers decide.

The island nation drew the ire of the U.S. Treasury Department two years ago after three suspected Iranian operatives were caught using their St. Kitts passports to launder money for banks in Tehran in violation of U.S. sanctions. It also had to recall more than 5,000 passports because they either didn’t include a place of birth or were issued to people who had changed their names. Since then a number of reforms have been made, but questions remain.

Peter Vincent: They’re not transparent programs. There are not safeguards in place.

Until 2014, Peter Vincent was the top legal adviser for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, part of the department of Homeland Security, which he says is well aware of all the vulnerabilities. In fact, the person in line to take over Homeland Security, General John F. Kelly, expressed concern in a report last year that “cash for passport programs could be exploited by criminals, terrorists or other nefarious actors.”

Steve Kroft: Does that present a security threat, do you think?

Peter Vincent: It does. In my opinion, the global community has established a very effective global security architecture to prevent terrorist attacks. I see these cash for citizenship programs as a gaping hole in that security architecture.

But it’s not stopped the programs from multiplying across the Caribbean…Dominica, Grenada, St. Lucia, and Antigua are all competing with St. Kitts now for customers and badly needed cash.

Gaston Browne: So what are we supposed to do? Sit back and do nothing? You tell me.

Gaston Browne, the prime minister of Antigua and Barbuda, says the revenue from its three-year-old program has kept the government from defaulting on its international loans and has turned the economy around. Antigua also claims to have among the strictest programs in the Caribbean. You actually have to show up here to get citizenship, albeit very briefly.

Gaston Browne: Our law provides them to spend at least five days here.

Steve Kroft: That sounds like a vacation.

Gaston Browne: Yes. I understand. But however, we have made sure that at least there must be some face-to-face contact so we know who these people are.

Steve Kroft: For five days.

Gaston Browne: Minimum.

Steve Kroft: What kinda people are you looking for?

Gaston Browne: We’re lookin’ for high net worth individuals. People who are established business people. Who are well-known. And to make sure that we get the crème de la crème.

If so, they are recruiting them in some odd places. Last summer, Antigua announced it was opening an embassy in Baghdad hoping to sell passports to Iraqis. It didn’t work out. But it’s doing better next door in Syria after hiring a relative of President Bashar Al-Assad to represent them.

Steve Kroft: Have you had any applications from Syria?

Gaston Browne: Yes. We have had applications from Syria.

Steve Kroft: And you’ve approved them.

Gaston Browne: Syria is one of the areas in which we have had some concerns but did not place it on a restricted list.

Prime Minister Browne told us instability breeds opportunity. Besides Syria, Antigua has sold citizenship to Iranians, Libyans, Pakistanis, and the people who brought condos in this half-built complex in the desert outside Dubai, 7,300 miles away from Antigua. Its website advertises, “Buy a villa in the UAE and get citizenship of Antigua.”

Steve Kroft: I mean, you said that you were looking for the crème de la crème.

Gaston Browne: Crème de la crème.

Steve Kroft: I mean, there’s a developer in Dubai.

Gaston Browne: Yes.

Steve Kroft: Sweet Homes.

Gaston Browne: Yes.

Steve Kroft: Who is advertising that he’s giving away passports to anyone who buys a condominium there.

Gaston Browne: You don’t believe that, right?

Steve Kroft: Like you open a bank account, you get a free toaster.

Gaston Browne: That is not so.

Browne dismissed the sweet homes ads as advertising hype, saying the citizenship is not free or guaranteed. Somebody has to come up with $250,000 for Antigua and condo buyers must pass a background check.

Gaston Browne: You have to go through all of the due diligence.

Steve Kroft: What kinda due diligence do you do?

Gaston Browne: Well, and that is where the crux of the matter lies.

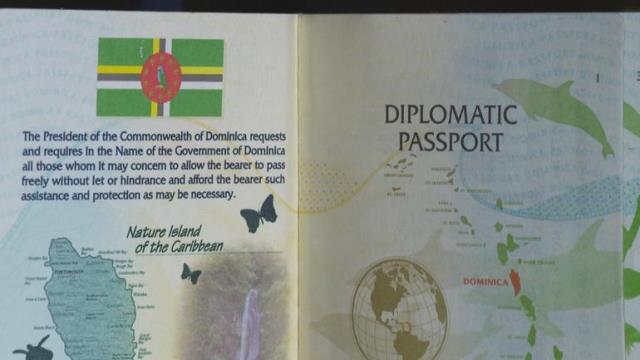

The prime minister claims that the names of all applicants for Antiguan citizenship are now screened by American intelligence and law enforcement agencies, and generally speaking due diligence in the Caribbean has improved substantially since the scandals in St. Kitts. The small island offices with a few people are now backed up by international firms that take the screening to a higher level. But ultimately it’s up to each country to decide who gets a passport, and the Caribbean has a rich history of turning a blind eye to official corruption. It’s affected the way the way passports are handed out, especially diplomatic passports, that entitle the bearer to all sorts of special privileges, which Peter Vincent says represents a much more serious security threat.

Peter Vincent: The border officials at the receiving country, even without a visa, almost always admit an individual carrying a diplomatic passport. In addition, border forces are not entitled to search the luggage of diplomats like they are for regular tourists. They simply wave them through.

The sale of diplomatic passports is not part of the citizenship by investment program, but it goes on under the table, particularly in Dominica which has had a most impressive corps of dodgy diplomats.

Lennox Linton: We had a diplomatic passport in the hands of Francesco Corallo, who, at the time, was on INTERPOL’s list of most-wanted criminals.

Parliamentarian Lennox Linton says no one in Dominica had ever heard of Corallo until he was stopped by authorities in Italy.

Lennox Linton: He said, “You can’t detain me. I’m a diplomat.” They said, “Diplomat? Diplomat of where?” He said, “Dominica.”

Then there’s Dominican diplomat Alison Madueke, a former Nigerian oil minister arrested for suspected bribery and money laundering. And Rudolph King, a Bahamian fugitive from U.S. justice, who was Dominica’s ambassador to Bahrain.

Lennox Linton: What we were doing with an ambassador in Bahrain, I don’t quite know. But they seem to think that there was some benefit in there for us.

Steve Kroft: I assume that you’ve asked the prime minister…

Lennox Linton: Yes.

Steve Kroft: How he ended up appointing these people, diplomats.

Lennox Linton: Yes.

Steve Kroft: And what was the answer?

Lennox Linton: The prime minister doesn’t answer those questions.

With vast sums of money flowing into these island nations, and more and more countries selling their citizenship, there is consensus that still more oversight and transparency is needed. But privacy and secrecy have always been a major selling point for people buying multiple passports, including Chris Kalin, the man who invented the business plan.

Steve Kroft: How many do you have?

Chris Kalin: I have multiple.

Steve Kroft: So you don’t wanna tell us how many you have?

Chris Kalin: There’s a few things in my life that, that I don’t talk openly about. And I keep for myself. But I am Swiss originally and many people think I’m very Swiss and so I’ll leave it at that.