Move likely marks last major change to US-Cuba policy before Obama leaves office

WASHINGTON – President Barack Obama is ending a longstanding immigration policy that allows any Cuban who makes it to U.S. soil to stay and become a legal resident, a senior administration official said Thursday.

The repeal of the “wet foot, dry foot” policy is effective immediately, according the official. The decision follows months of negotiations focused in part on getting Cuba to agree to take back people who had arrived in the U.S.

“The Department of Homeland Security is ending the so-called ‘wet-foot, dry foot’ policy, which was put in place more than 20 years ago and was designed for a different era,” Obama said in a statement. “Effective immediately, Cuban nationals who attempt to enter the United States illegally and do not qualify for humanitarian relief will be subject to removal, consistent with U.S. law and enforcement priorities.”

The president said U.S. authorities will now treat Cuban migrants “the same way we treat migrants from other countries.”

Andy Gomez, a retired university of Miami professor and Cuba expert, is speaking about the benefits from the Cuban American Adjustment act.

“This was probably the one issue and Washington and Havana agree on because of the many abuses we have seen throughout the years,” Gomez said.

Meanwhile, South Florida’s Cuban American elected officials are slamming the move.

“President Obama has found one more way to frustrate the democratic aspirations of the Cuban people and provide yet another shameful concession to the Castro regime,” U.S. Rep. Mario Diaz-Balart, R-Fla., said in a statement.

U.S. Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, R-Fla., issued a statement against the move, saying in part, “In another bad deal by the Obama administration, it has traded ‘wet foot, dry foot’ for the elimination of an important program (Cuban Medical Professional Parole Program) which was undermining the Castro regime by providing an outlet for Cuban doctors to seek freedom from forced labor which only benefits an oppressive regime.”

The official said the Cubans gave no assurances about treatment of those sent back to the country, but said political asylum remains an option for those concerned about persecution if they return.

Local 10 News reporter Todd Tongen spoke to some locals Thursday in Little Havana. They gave their thoughts on the repeal.

“I’m happy because the Cubans should stay in Cuba and fight to do away with the communist regime in Cuba, and not come here and do nothing about it,” one man said. “And I know they don’t do nothing about it, because it’s been 58 years.”

“It’s going to be good for the immigration in the United States because it’s going to limit the immigration,” another man said. “It’s going to be bad for the Cuban people because they cannot come here at their will.”

President-elect Donald Trump has taken a tougher line on U.S. relations with Cuba and could undo the change once he takes office.

The “wet foot, dry foot” policy was put in place in 1995 by President Bill Clinton as a revision of a more liberal immigration policy. Until then, Cubans caught at sea trying to make their way to the United States were allowed into the country and were able to become legal residents after a year. The U.S. was reluctant to send people back to the communist island then run by Fidel Castro, and the Cuban government also generally refused to accept repatriated citizens.

The Cuban government has in the past complained bitterly about the special immigration privileges, saying they encourage Cubans to risk dangerous escape trips and drain the country of professionals. But it has also served as a release valve for the single-party state, allowing the most dissatisfied Cubans to seek better lives outside and become sources of financial support for relatives on the island.

The changes would be the latest step by Obama to normalize relations with Cuba.

Relations between the U.S. and Cuba were stuck in a Cold War freeze for decades, but Obama and Cuban President Raul Castro established full diplomatic ties and opened embassies in their capitals in 2015. Obama visited Havana last March.

U.S. and Cuban officials were meeting Thursday in Washington to coordinate efforts to fight human trafficking. A decades-old U.S. economic embargo, though, remains in place as does the Cuban Adjustment Act which lets Cubans become permanent residents a year after legally arriving in the U.S.

The official said that in recent years, most people fleeing the island have done so for economic reasons or to take advantage of the benefits they know they can receive if they make it to the U.S.

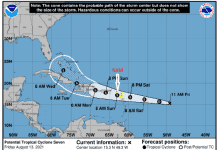

The official also cited an uptick in Cuban migration, particularly across the U.S.-Mexico border — an increase the official said reflected an expectation among Cubans that the Obama administration would soon move to end their special immigration status.

Since October 2012, more than 118,000 Cubans have presented themselves at ports of entry along the border, according to statistics published by the Homeland Security Department. During the 2016 budget year, which ended in September, a five-year high of more than 41,500 people came through the southern border. An additional 7,000 people arrived between October and November.

The influx has created burdens on other countries in the region that must contend with Cubans who have yet to reach the U.S. border, the official said.

The Cuban Medical Professional Parole Program, which was started by President George W. Bush in 2006, is also being rescinded. The measure allowed Cuban doctors, nurses and other medical professionals to seek parole in the U.S. while on assignments abroad.

People already in the pipeline under both “wet foot, dry foot” and the medical parole program will be able to continue the process toward getting legal status.

The preferential treatment for Cubans reflected the political power of Cuban-Americans, especially in Florida, a critical state in presidential elections. That has been shifting in recent years. Older Cubans, particularly those who fled Castro’s regime, tend to reject Obama’s diplomatic overtures to Cuba. Younger Cuban-American voters have proven less likely than their parents and grandparents to define their politics by U.S.-Cuba relations.

Exit polls show President Barack Obama managed roughly a split in the Florida Cuban vote in 2012, and Trump in November won the same group by a much narrower margin than many previous Republican nominees.